Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

I. THE IP DILEMMA

A. What is an NFT?

B. Then & Now

II. PUNKS NOT DEAD

A. Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus

B. Monkey Business

III. MARK OR MOCKERY?

A. Bad Subjects

IV. CONCLUSION: TO THE MOON

INTRODUCTION

Everybody’s talking about NFTs, but they don’t know what they’re saying—especially when it comes to ownership. NFTs were the boom of 2021, the bust of 2022, and the enigma of 2023. Some people love them, more people hate them, but most people just find them confusing. After all, why would anyone spend $100,000 to own a monkey JPEG, when you can download it for free on the internet?

Intellectual property lawyers are especially confused, because they thought they understood how creative markets worked, until NFTs came along. Sure, NFTs present lots of legal questions, and intellectual property law answers many of those questions.1 But the answers are peculiarly unsatisfying. Copyright law says NFT artists own the digital images they create. Fine. But what does that mean when artists use algorithms to generate 10,000 similar images, and then sell the images to collectors? Trademark law says NFT artists own the distinctive marks they use in commerce, just like anyone else. No problem. But what happens when artists try to license their brand to their collectors?

I. THE IP DILEMMA

In the NFT market, copyright and trademark law often provide the right answers to the wrong questions. That’s a problem, because copyright and trademark are both forms of competition policy, intended to solve market failures by reducing transaction costs on producing, distributing, and consuming content.2 But technological change has changed the market failures. Many of the transaction costs copyright and trademark were designed to reduce have disappeared. It’s nice to know who owns the copyright in an image, but what if no one cares? It’s great for artists to control their brands, but what if no one’s confused?

When lawyers and law professors look at NFTs, they tend to see a copyright market. I think they’re mistaken. The NFT market shows us that the art market has always been a market for brands, and suggests that the market for other creative goods could be as well. After all, authors were always selling their brand, copies were just a way of monetizing it. But it was never very efficient and left lots of money on the table. There’s got to be a better way. Maybe the NFT market suggests there is.

Historically, copyright and trademark were complements that authors used to build a career. Trademark helped them grow their brand by limiting competition, and copyright enabled them to monetize their brand by selling copies of their work. Unfortunately, there were a lot of transaction costs on selling copies that copyright couldn’t fix, like the cost of making copies, distributing them to stores, and getting consumers to buy them. It’s no secret that technology has reduced or even eliminated those costs. Reproducing and distributing digital works is free, and social media can make brand-building free as well. After all, YouTube and TikTok have created many celebrities, by giving them direct access to consumers via the equivalent of broadcast media. The medium is the massage, and it feels great.

If the problems copyright was designed to solve are gone, why do we even need it anymore? The primary reason is to ensure authors have the exclusive right to monetize their product. Copyright creates control, and control ensures authors get paid. But what if there were a way for authors to get paid more? Copyright enables authors to monetize their brands by selling copies. But what if authors could monetize their brand by selling shares in their celebrity? A securities market in fame would give creators access to the capital markets, and enable them to capture a much larger percentage of the social value they generate.

Where does that leave intellectual property lawyers? In a great place. While copyright is rapidly becoming obsolete, trademark is only becoming more important. If the new creative market is for securitized brands, then authors will need help understanding, developing, protecting, and negotiating their brand relationships.

We can already see it happening. While everyone assumes the NFT market is primarily a copyright market, all of the high-profile litigation is trademark litigation. It’s because the value is in the brand, not the copies. I’ll use several examples of NFT trademark litigation to illustrate my thesis. And then I’ll reflect on how the Supreme Court’s decision in Jack Daniel’s v. VIP Products could affect the development of this new market.

A. What is an NFT

In a nutshell, an NFT is an entry on a cryptographic ledger or “blockchain” that represents something other than a quantity of the native currency of that blockchain. For example, an entry on the Ethereum blockchain usually represents a quantity of Ether, the native currency of the Ethereum blockchain, but an Ethereum NFT represents something else, anything else. In theory, NFTs can exist on any blockchain capable of recording data other than a quantity of currency. But, most NFTs are recorded on blockchains designed for NFTs, like Ethereum, Solana, and Tezos. NFTs have two essential features: uniqueness and ownership. Every NFT has a unique token ID and belongs to a particular wallet. Token IDs make it impossible to copy NFTs, and cryptography makes it impossible for anyone other than the wallet owner to transfer an NFT.

While an NFT can consist of any quantity of data, writing data on a blockchain is expensive, so most NFTs are as small as possible. Usually, an NFT consists of little more than a token ID, a transaction history, and a URL pointing to whatever the NFT represents. NFT technology already has many different uses, and doubtless many more will develop in due course. Already, NFTs are used for supply chain management, financial settlement, gaming, and identity verification, among other things. But the biggest and best-known use of NFTs is for authenticating digital art.

While NFTs can represent literally anything, the overwhelming majority of NFTs represent digital images. Or rather, most NFTs represent “ownership” of a digital image. I use scare quotes because ownership of an NFT of a digital image usually doesn’t mean ownership of the copyright in the digital image.

B. Then & Now

NFTs began with Bitcoin. On August 18, 2008, someone registered the domain name bitcoin.com, and on October 31, someone using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto posted a link to a short article titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System on a cryptography mailing list. Nakamoto created the Bitcoin blockchain on January 3, 2009 by mining the first block, and the rest is history. Bitcoin made the concept of cryptocurrency a reality, and led to the development of many other blockchains, with different functionalities, including blockchains designed to record data other than cryptocurrency transactions. For example, Namecoin was intended to record URLs.3

While there’s considerable disagreement about who created the first NFT, digital artist Kevin McCoy is a plausible contender.4 Before the NFT market, it was hard for digital artists to sell their artworks to collectors. Why? There’s no such thing as an original, because every copy of a digital artwork is identical. Paintings and sculptures are unique objects, but digital images aren’t. Of course, digital artists could sell certificates of authenticity, but collectors weren’t biting. Maybe certificates of authenticity didn’t feel like “real” ownership, or maybe digital artists selling pieces of paper was a little too ironic even for art collectors.

McCoy wanted to sell his digital artworks, and was looking for a digital alternative to certificates of authenticity. In 2014, he realized that he could use the Namecoin blockchain to create a transferrable cryptographic record of the provenance of an artwork. While the purpose of the Namecoin blockchain was to register .bit domain names and create a decentralized domain name system, it could be used to record any kind of data, including information about the ownership of an artwork. So McCoy registered a Name on the Namecoin blockchain, and stated that ownership of the blockchain entry constituted ownership of his digital artwork Quantum. In other words, he created a cryptographic certificate of authenticity. It was the “first NFT,” because it was the first time someone used a blockchain entry to represent ownership of a work of art.5

Excited by the potential of cryptographic certificates of authenticity, McCoy founded Monegraph, a company dedicated to helping artists create and sell cryptographic certificates of authenticity.6 Unfortunately, he was ahead of his time, and his concept didn’t immediately catch on. Part of the problem was that it relied on the Namecoin blockchain, which provided that Name registrations would automatically expire after about a year, unless they were renewed. You can lose a paper certificate of authenticity, but at least they aren’t written in disappearing ink. Ironically, the Name McCoy registered for Quantum expired when he failed to renew it, which became an issue when the NFT market took off, and Free Holdings Inc. registered the same Name. McCoy created a new NFT of Quantum on the Ethereum blockchain, which was intended to represent both ownership of the artwork and the expired Namecoin NFT. The new owner of the Name claimed to own Quantum and sued McCoy for slander of title, among other things. While the district court dismissed the action, the plaintiff intends to appeal.7

In any case, the dispute subtly presents a question everyone is avoiding. When an artist sells an artwork, what is the artist actually selling? Or rather, what makes provenance “real?” Free Holdings and McCoy don’t dispute the facts, but what those facts mean. There’s no question that McCoy registered the Name that Free Holdings now owns, and said it represented ownership of Quantum. The only real question is whether he still thinks it represents Quantum, and whether he can change his mind. In other words, the question is whether McCoy should be compelled to endorse ownership of the Name as meaning ownership of Quantum, whatever that means.

The district court dismissed Free Holdings’s complaint, holding that there was no real dispute, because Free Holdings claims to own one blockchain entry, and McCoy sold a different blockchain entry. But that misses the point. The question is what it means to “own” an artwork, what it means for a blockchain entry to represent ownership of an artwork, and what it means for a blockchain entry to remain the “same” “entry.” None of these questions have easy answers. Maybe they’re unanswerable. Or maybe we’re asking the wrong questions. In any case, it’s time to move on.

II. PUNKS NOT DEAD

CryptoPunks created the NFT market. In June 2017, Larva Labs released the CryptoPunks NFT collection, which consisted of 10,000 NFTs, each of which represented “ownership” of a digital image.8 The images were styled to resemble 8-bit sprites, with a retro aesthetic based on 80s video games and 90s cyberpunk. Each image consisted of a profile picture, with different features or “traits” generated by an algorithm.

When Larva Labs created the CryptoPunks NFT collection, anyone could claim one of the NFTs for free, simply by paying the “gas” fee to mint the NFT on the Ethereum blockchain, which at the time was about 11 cents. Initially, demand for the CryptoPunks NFTs was sluggish, but it soon picked up. Before long, all of the NFTs were claimed, and as demand continued to increase, the price of CryptoPunks NFTs on the secondary market quickly rose. Currently, the “floor” price for a CryptoPunks NFT is about $100,000, and “rare” examples have sold for millions of dollars.9

Success loves company, especially when it promises money for nothing and clicks for free. Before long, CryptoPunks became the paradigmatic NFT collection, effectively defining the NFT market. NFT collectors wanted NFTs of procedurally- generated digital images that were easy to use as profile pictures or “PFPs,” and the market delivered on their expectations.

Most popular NFT collections consist of generative PFPs, many NFT collections copy the CryptoPunks 8-bit aesthetic, and quite a few NFT collections simply copy the CryptoPunks images, often without changing them at all.10 For example, the CryptoPhunks NFT collection literally consists of the 10,000 CryptoPunks images flipped from right to left. In March 2021, singer-songwriter Jonathan Mann identified at least 57 CryptoPunks-themed NFT collections before stopping count.11 And the number of knockoff CryptoPunks NFTs has only ballooned since then. Unsurprisingly, when a clever coder devised a way to create NFTs on the Bitcoin blockchain, the first popular Bitcoin NFT project was Ordinals, which is literally just Bitcoin NFTs of the CryptoPunks images.

So, why didn’t the owners of the CryptoPunks images and brand object to all of this blatant copying? It would be easy to file copyright and trademark infringement claims against the knockoff NFT collections, despite some copyrightability concerns.12 They certainly seem to value their intellectual property rights. Larva Labs retained all of its intellectual property interests in the CryptoPunks, until it sold them to Yuga Labs in 2022, which licensed at least some of those rights to the owners of the CryptoPunks NFTs.

What does that mean in practice? Larva Labs valued its copyright in the Cryptopunks images and its trademark in the Cryptopunks brand enough to keep them, rather than give them to CryptoPunks NFT owners or place them in the public domain. And Yuga Labs valued the CryptoPunks copyrights and trademarks enough to buy them for an undisclosed, but presumably quite substantial, sum of money.

And yet, neither Larva Labs nor Yuga Labs has done much of anything to stop people from creating knockoff CryptoPunks NFT collections. Yes, Larva Labs briefly made a desultory effort to prevent the sale of the most egregious knockoffs, filing DMCA Section 512 takedown notices with prominent NFT marketplaces like OpenSea.13 But it never followed up with lawsuits, and eventually seems to have stopped bothering with the takedown notices. Yuga Labs is even more open- minded. It seems perfectly happy to let people create all of the CryptoPunks knockoffs they like.

What gives? I suspect Larva Labs eventually came to realize what Yuga Labs already knew: The only thing worse than being copied is not being copied. Or rather, the entire point of NFTs is that everyone knows what is real and what is “fake.” When people created knockoff CryptoPunks NFT collections, everyone knew they were knockoffs. Everyone who bought them, bought them because they were knockoffs, because they thought that particular knockoff was interesting and might become valuable. They bought the knockoffs because the CryptoPunks brand was cool and desirable, and the knockoffs traded on that cool, at a remove.

Or rather, why is art valuable? Because people are talking about it and copying it. The undeniable truth of the NFT market, like any art market, is that if you aren’t being copied, you are irrelevant. Larva Labs objected to people copying the CryptoPunks because they felt like they didn’t have a choice. But Yuga Labs knew better. When you’re selling clout, copying is great, because it only underscores your cool. And NFTs ensure you don’t have to worry about forgeries diluting the market for your originals. The copycats are making money by pumping your brand, why not cry all the way to the bank?

A. Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus

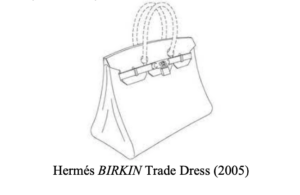

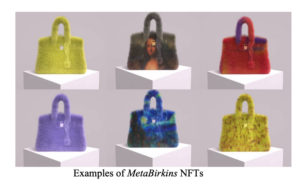

While NFT brands like CryptoPunks quickly learned to love knockoffs, legacy brands tend to be more skeptical. For example, when NFT artist Mason Rothschild created his Metabirkins NFT collection, which consisted of digital images of handbags riffing on the iconic Hermes Birkin bag, Hermes was not amused, and sued him for trademark infringement.14

Hermes is a luxury brand known for many different products, but especially its Birkin handbag, named for the actress and singer Jane Birkin. In 1984, Birkin was flying from Paris to London. She was using an open straw bag as a carryon, and when she put it in the overhead bin, everything fell out. Fortuitously, she was seated next to Jean-Louis Duman, the CEO of Hermes, who was inspired to create a leather bag with a secure closure, which he named after Birkin. The Birkin bag became a status symbol, and new Birkin bags currently cost more than $20,000, when they are even available.

In May 2021, artist Mason Rothschild created a digital animation titled Baby Birkin, which he sold as an NFT for about $23,500.15 Based on the success of Baby Birkin, Rothschild created the MetaBirkins NFT collection, which consists of 100 NFTs of imaginary Birkin bags. The Metabirkins NFTs were also popular, and Hermes inevitably noticed.

In a nutshell, Hermes alleged that Rothschild used its Birkin name mark and Birkin bag trade dress without permission, confusing consumers about the source of his NFTs and diluting the famous Birkin mark. After all, Rothschild obviously used the name MetaBirkins and created images that resembled Birkin bags because he wanted to associate his NFTs with the Birkin brand. According to Hermes, Rothschild was just free-riding on the consumer goodwill associated with the Birkin brand in order to sell his NFTs. Hermes planned to sell its own NFTs, and Rothschild’s Metabirkins NFTs were unfairly stealing its customers. Even worse, copycats were already selling knockoff MetaBirkins NFTs, creating more unfair competition and further diluting the brand.

There’s a problem. It’s true that Rothschild used the Birkin mark and trade dress in order to sell his NFTs. But no one was actually confused. Everyone who bought a MetaBirkins NFT knew exactly what they were getting, to the extent anyone knows what they’re getting when they buy an NFT. The consumers who bought MetaBirkins NFTs wanted to buy NFTs created by Rothschild, not NFTs created by Hermes. Rothschild wasn’t selling Birkin bags, he was selling art, albeit in the form of NFTs associated with digital images.

Accordingly, Rothschild’s defense relied primarily on Rogers v. Grimaldi, arguing that his use of the Birkin mark and trade dress was a fair use protected by the First Amendment.16 The Rogers court held that trademark law “does not bar a minimally relevant use of a celebrity’s name in the title of an artistic work where the title does not explicitly denote authorship, sponsorship, or endorsement by the celebrity or explicitly mislead as to content.”17 The so-called “Rogers test” is generally understood to mean that “artistically relevant” uses of a mark are non- infringing, even if some consumers might find the use confusing.

Rothschild argued that his use of the Birkin marks in the MetaBirkins NFTs was noninfringing because the MetaBirkins NFTs were artworks, and using the Birkin marks was the only way to create the MetaBirkins NFTs. In other works, his use of the Birkin marks was “artistically relevant” because it was essential to his expressive speech commenting on the social meaning of the Birkin marks.

For better or worse, the district court denied Rothschild’s motion for summary judgment, and the case went to trial. The jury found for Hermes and awarded it $133,000 in damages. Rothschild’s appeal is pending.

Once again, the tension between trademark doctrine and the realities of the NFT market is palpable. Was Rothschild using the Birkin marks in order to market and sell his MetaBirkin NFTs? Of course. Was anyone confused about what he was selling and what they were buying? Of course not. The question is what kinds of speech trademark law is intended to control, and when trademark law’s control of speech is consistent with the First Amendment.

Why did Hermes object to Rothschild’s use of the Birkin marks? Its objections would obviously be justified if Rothschild were using the Birkin marks to sell counterfeit Birkin bags. But he wasn’t. He was using the Birkin marks to sell NFTs of digital images of obviously fake Birkin bags. No one who bought or even considered buying a MetaBirkins NFT thought the MetaBirkins NFTs were produced or endorsed by Hermes. On the contrary, people wanted to buy MetaBirkins NFTs precisely because they thought the NFT collection was a funny joke, perhaps at the expense of Hermes. Some people may have purchased MetaBirkins NFTs because they like Hermes, and saw the MetaBirkins NFTs as a funny riff on something they like.

But let’s be real. Collectors bought MetaBirkins NFTs primarily because they thought Rothschild is a clever artist and his artworks are likely to be more valuable in the future. In other words, collectors were buying Rothschild referencing Birkin, the same way collectors buy Warhol referencing Campbell’s Soup.

Yes, Rothschild used the Birkin brands. But he didn’t use them in a way that unfairly competed with Hermes’s use of the brands. And he didn’t use them in a harmful way, or at least not in a way the law ought to recognize as actionably harmful. If anything, Rothschild arguably increased the clout of the Birkin brands, by making them the subject of the first NFT brand litigation.

Or rather, when Hermes sells Birkin bags, it’s selling the Hermes brand. When Rothschild sold Metabirkins NFTs he was really selling the Rothschild brand. If Hermes wanted to sell Birkin NFTs, it could easily do so, if anyone wanted to buy them. And Rothschild’s Metabirkins NFTs wouldn’t affect Hermes’s NFTs, except insofar as they made Hermes look foolish. But making a company look foolish is precisely the kind of speech the First Amendment is supposed to protect.

B. Monkey Business

For better or worse, one of the most popular NFT collections is the Bored Ape Yacht Club (“BAYC”) NFT collection created by Yuga Labs in 2021. The BAYC collection is similar to the CryptoPunks collection, in that it consists of 10,000 NFTs, each of which represents “ownership” of a procedurally-generated image of a cartoon ape. Yuga Labs launched BAYC for presale on April 21, 2021, selling the NFTs for 0.08 ETH, which was about $190 at the time. Initially, sales were slow, because collectors didn’t know what the images would look like. But when they released the BAYC images on April 30, the entire collection sold out in about 12 hours.18 Prices on the secondary market started rising almost immediately. The current floor price for a BAYC NFT is over $100,000, and some BAYC NFTs have sold for millions. What’s more, many celebrities—and at least one law professor—became BAYC NFT owners.19

Just like the CryptoPunks, knockoff projects proliferated, two of the most prominent being the PHAYC and Phunky Ape Yacht Club (“PAYC”) collections.20 Much like Larva Labs, Yuga Labs was open-minded about copycats. It sent some takedown notices, but mostly let them have their fun. After all, nothing pumps an NFT brand like people selling ripoffs.

So, whatever, BAYC is just CryptoPunks with different pictures. Not so fast. For one thing, the pictures matter. Many NFT collectors love CryptoPunks and hate BAYC or vice versa. And there are plenty of other NFT projects competing for their attention, which they might like better. For another, Larva Labs and Yuga Labs took very different approaches to their intellectual property rights, whatever those rights might be.

Larva Labs said it was in the business of selling NFTs, and that’s it. When you bought an NFT, that’s what you got, whatever it is, nothing more. You didn’t get any copyright interest in the image associated with your NFT, and you certainly didn’t get any trademark interest in the CryptoPunks brand.

Yuga Labs took the opposite approach. It gave NFT owners “commercial rights” in their NFTs.21 What does that mean? Your guess is as good as mine, but Yuga seems to have understood it to mean a copyright license to use the image associated with the NFT and a trademark license to use something to promote your own brand. The “something” was left unstated. But the upshot was that Yuga didn’t really care. It wanted NFT owners to use the BAYC brand as much as possible. Hell, it was almost begging NFT owners to use the BAYC brand, especially celebrity NFT owners.

Yuga Labs was clever. It realized that the value of BAYC was the brand. And it realized that its only asset was the BAYC brand. Why not let NFT owners use the brand to sell their own brand? It was all upside for BAYC. It’s impossible for your licensee to compete with your market when you aren’t selling anything but your brand.

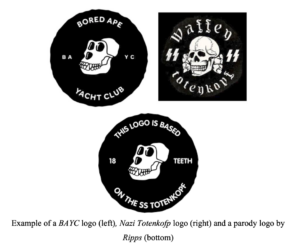

Oh no, there was a problem. What if the brand was toxic? From the beginning, many people found the BAYC images distasteful. But conceptual artist Ryder Ripps made it his mission to identify all of the distasteful elements of the BAYC images and show that BAYC is really a crypto-fascist troll. Ripps observed that the BAYC logo resembles the Nazi Totenkopf logo. He observed that the BAYC images use many racially-coded elements. And I mean, come on. It’s a bunch of monkey cartoons.

Whatever. People can disagree about what images mean and about what is or should be offensive. At first, Yuga just ignored Ripps’s criticism. If you can’t fight ‘em, join ‘em, or something like that. At least he was talking about BAYC, whatever he was saying.

At least for a while, it worked. Collectors more or less ignored Ripps’s criticisms of BAYC. But he wasn’t done. If criticism didn’t get their attention, maybe competition would.

So Ripps created his own collection of BAYC NFTs in order to troll Yuga, by using them to highlight his argument that the BAYC images are racist trash.22 At least at first, the RR/BAYC NFTs were bespoke. Ripps took requests on Twitter, and created NFTs only if he thought the requester deserved one. In the tradition of good pranks, Ripps’s fake BAYC collection was successful. Alan Abel, eat your heart out. Many people bought Ryder Ripps’s RR/BAYC NFTs, maybe because they believed in the project and maybe because they wanted to make money. Who cares, it was expressive either way. Of course, it was also profitable. And it got Ripps’s criticisms of BAYC lots of attention.

Eventually, Yuga decided it couldn’t keep ignoring Ripps. On June 24, 2022, Yuga Labs sued Ripps for trademark infringement.23 Why trademark infringement rather than copyright? After all, Ripps literally copied the BAYC images and used them to sell his own NFTs, so copyright infringement would have been trivially easy to prove. Sure, Yuga didn’t sue any other copycats for copyright infringement, but that’s irrelevant. Copyright doesn’t care if you pick and choose who you sue for infringement.

Of course, Yuga technically couldn’t sue for copyright infringement when it filed its complaint, because it hadn’t registered the BAYC images with the Copyright Office. But it wasn’t a real impediment. After all, the Copyright Office offers expedited registration in order to enable copyright owners to sue for unanticipated infringement. Maybe Yuga was worried about whether the BAYC images were copyrightable or whether it was actually the copyright owner, given that it had given “commercial rights” in the images to NFT owners.24

I suspect the reason Yuga sued Ripps for trademark infringement rather than copyright infringement was that Yuga cares about its brand, not its ability to control the use of individual BAYC images. From Yuga’s perspective, copyright infringement is great. The more people who see the BAYC images, the better it is for the BAYC brand. But Ripps’s criticisms of the BAYC images were hurting the brand, and hurting it badly. Many of BAYC’s celebrity owners stopped promoting the brand and got rid of their BAYC NFTs.25 Nobody wants to be associated with neo-Nazi racism, even if they’re just allegations.

On their face, Yuga’s trademark infringement claims against Ripps and his business partner Jeremy Cahen are pretty compelling. Ripps used not only the Bored Ape Yacht Club and BAYC word marks, but also many BAYC design marks, all in order to sell his own NFTs of the BAYC images. Sure, the BAYC marks weren’t yet registered and there’s some question about whether and how the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) will register NFT marks. But as a practical matter, Yuga used the BAYC marks in commerce to sell NFTs, and Ripps used the same or similar marks in commerce to sell identical NFTs. It should be slamdunk for Yuga.

Not so fast. Just like Rothschild, Ripps relied on Rogers. Sure, the RR/BAYC NFTs are identical to the BAYC NFTs. But according to Ripps, the entire RR/BAYC collection is a work of conceptual art, and the only way to realize the concept is to copy the BAYC NFTs. In other words, Ripps characterizes his use of the BAYC brand as an expressive use, not an infringing use. Initially, it seems bananas. But on reflection, maybe not so much. After all, no one was confused about the source of the RR/BAYC NFTs. That was the entire point of creating the collection. What’s more, NFT technology ensures that buyers know the RR/BAYC NFTs aren’t “real” BAYC NFTs. It’s like selling a product indelibly marked “counterfeit.” Even if it otherwise looks identical to the real thing, no one will be confused.

Regardless, the court denied Ripps’s motion to dismiss and seems skeptical of his Rogers defense. I suspect Ripps won’t fare any better than Rothschild. Courts have taken to heart Justice Holmes’s observation, “[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations.”26 It goes in spades for conceptual art. The court is unlikely to care what Ripps intended the RR/BAYC NFTs to mean or what RR/BAYC collectors understand them to mean. The question before the court is whether Ripps infringed Yuga’s trademarks, not whether he created conceptual art. Or at least, that’s how the court is likely to see it. Like a joke, conceptual art isn’t amusing if you have to explain it.27

And yet, even if Yuga wins, it will be a Pyrrhic victory. The damage to its BAYC brand is done, and can’t be undone. If anything, Yuga only made it worse by suing Ripps, who has used the lawsuit to amplify his criticisms of BAYC. It’s a perfect example of the Streisand Effect. If Yuga had only kept ignoring Ripps, fewer people would have noticed him, and he might eventually have moved on. By suing him, Yuga only amplified his criticisms by turning them into news.

III. MARK OR MOCKERY?

There’s an inevitable tension between trademark law and free expression. The Lanham Act gives trademark owners the exclusive right to use their mark in commerce.28 But marks don’t just communicate information about the source of goods and services. They communicate all different kinds of meaning. Indeed, as Ed Timberlake has observed, trademarks are truly the most poetic form of intellectual property, because their meaning ultimately depends on consumers. A mark means whatever its audience understands it to mean, irrespective of what the owner of the mark wants it to mean.

Courts struggle to reconcile the commercial interests of trademark owners with the expressive interests of the public. Trademark owners want to use their marks in order to develop and protect consumer goodwill. But consumers are entitled to use marks to talk about the world of commerce in which they are immersed.

Trademark law has developed a congeries of doctrines intended to resolve or at least mitigate that tension, including the concepts of nominative use and descriptive use. Broadly speaking, a trademark owner’s exclusive right to use their mark extends only to use of the mark as a mark, and doesn’t include use of a mark simply to identify or describe the product or service associated with the mark.

But the expressive value of marks is large and contains multitudes of expressive possibilities. Sometimes, it’s easy to know whether a mark is being used as a mark or as an expression. But often, it’s hard. It gets particularly hard when someone uses a mark in order to sell a product or service, but also in order to comment on the expressive content of the mark.

The problem is often framed as one of “trademark parody,” but it’s much broader. Parody is just one literary genre used to make critical commentary, among a wide range of critical genres. Courts have struggled to determine whether and when trademark parodies are protected speech, as opposed to mere trademark infringement. And they struggle even more with subtler genres. What happens when consumers might not understand the joke, or even understand that it is a joke? And what happens when it isn’t a joke, but an allusion or a metaphor? The courts aren’t ready for such subtleties. But the Supreme Court is currently confronting the question of trademark parody and when it’s protected speech.

A. Bad Subjects

As a great philosopher once observed, “There’s no such thing as bad publicity.”29 Or rather, as another great philosopher responded, “The only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.”30 Of course, both may have eventually had second thoughts.

In any case, businesses love publicity, until they don’t. Sometimes, businesses dislike publicity for good reason, because it makes them look bad. Other times, they dislike publicity because they don’t understand it. And occasionally, they dislike publicity because they feel like someone is profiting from their commercial goodwill without their permission.

That’s usually why brands object to parodies. They know the parody is a joke, but they don’t think it’s funny. Or rather, they don’t think it’s funny that someone else is making money by making fun of their brand.

Currently, the butt of the joke is Jack Daniel’s Properties, which sued VIP Products for making fun of its brand.31 Jack Daniel’s famously makes whiskey and VIP not-so-famously makes novelty dog toys, most of which poke fun at famous brands. Essentially, VIP’s business model is to make dog toys that look like familiar products, but with altered labels that refer to dogs in an arguably humorous fashion. Jack Daniel’s most popular product is its flagship whiskey, the label of which reads, “Jack Daniel’s Old No. 7 Brand Tennessee Sour Mash Whiskey.” VIP sold a dog toy in the shape and color of a Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle, with a printed label similar in appearance to the Jack Daniel’s label, which read, “Bad Spaniels The Old No. 2 On Your Tennessee Carpet.” Ha ha.

Anyway, Jack Daniel’s filed a trademark infringement action against VIP. The district court granted Jack Daniel’s motion for summary judgment, holding that VIP’s Bad Spaniels dog toy was likely to cause consumer confusion and tarnish the Jack Daniel’s brand. But the 9th Circuit reversed under Rogers, holding that VIP’s use of the Jack Daniel’s marks wasn’t “explicitly misleading.”32 The Supreme Court granted certiorari and heard oral argument in Jack Daniel’s v. VIP Products on March 22, 2023.33 It’s anyone’s guess how the Court will decide the case. But its decision is almost certain to affect the outcome in Rothschild’s appeal and Yuga’s action against Ripps.

As usual, Jack Daniel’s v. VIP Products seems to present a lot of complicated questions about trademark doctrine. But the real question is about the tension between trademark law and the First Amendment. Should trademark owners be able to prohibit the expressive use of their marks to sell products? After all, VIP Products obviously used the Jack Daniel’s brand to sell its dog toys, but consumers obviously weren’t confused. Should Jack Daniel’s be able to use trademark law to prevent VIP Products from free riding on its brand, even though VIP Products isn’t competing with Jack Daniel’s?

Rothschild and Ripps pose the same question. Both used a famous brand in order to sell their own product that critically commented on the famous brand. Obviously, the First Amendment protects the right to criticize a brand. Jack Daniel’s whiskey is mediocre, Birkin bags are basic, and BAYC is racist. But VIP, Rothschild, and Ripps did more. They sold products. Should the First Amendment protect the right to criticize a brand by selling products that use the brand to criticize it?

IV. CONCLUSION: TO THE MOON

The First Amendment question is obviously important. But it’s just as obvious how it should be decided.34 Trademarks exist to protect consumers, not to protect brands. Consumers aren’t stupid. Or at least, they understand brands. They ought to, they’ve spent their whole lives consuming them. Consumers understand and value comically trivial distinctions between branded products. Indeed, consumers often understand brands better than brand owners.

So, should trademark owners be able to prohibit the use of their marks when consumers aren’t confused? Of course not. The only legitimate purpose of trademark law is to ensure that consumers know what they are getting. As soon as trademark owners have to invoke hypothetical consumers and introduce consumer surveys, you know they are lying in order to prevent competition, or even worse to suppress criticism. The “idiot in a hurry” has always been the judge, eager to enable trademark rent-seeking, rather than ask what trademark law is supposed to accomplish in the first place.

Why dwell on these easy questions? Why not ask what they tell us about the future of trademarks and the market for expression? We live in the Information Age, but haven’t yet fully internalized what that means. For most of human history, we lived in a world where information was scarce and expensive. When we invented the printing press, which made the reproduction and distribution of information a little cheaper, we also invented copyright, which was intended to encourage investment in the reproduction and distribution of information. But information always wanted to be free. And now it is, if we let it. Digital media and the internet promise that we all really can consume whatever we want, whenever we want, however we want.

Of course, we will never stop consuming physical goods. But the most valuable goods we consume are brands, not products. Trademark law assumes that marks identify the products we consume. But in reality, trademarks are the product we consume. And if consumers are happy with what they get, why should the law disagree with them?

The NFT market is the vanguard of this new market in brands, because it shows us that consumers want their brands neat.35 Why do people buy NFTs? For the clout, the same reason they’ve always cared about brands. The only difference is that NFTs enable consumers to buy clout without buying anything else. Consumers buying clout aren’t confused about what they’re getting. There’s no reason the law should talk down to them.

* Spears-Gilbert Professor of Law, University of Kentucky College of Law.